The Rise and Fall of Jobriath, Rock’s First Openly Gay Star

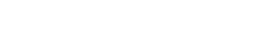

In every walk of life, someone has to go first and, as a result, often doesn’t see the fruits of their labor and tends to be forgotten as the world moves on. So it seemed to be for Jobriath, the first openly gay musical artist signed to a major label. He arrived with all guns blazing in 1973, describing himself as “rock’s first true fairy” and pioneering a form of art-rock blended with vaudeville that simply bemused most listeners. And while he was the victim of prejudice, several other factors contributed to his disappearance from the scene after releasing just two albums.

Born Bruce Wayne Campbell in 1946, Jobriath showed a talent for music from an early age, playing organ in the church in his Pennsylvania hometown and composing the first half of a classical symphony in high school. He discovered folk music and fell in with the psychedelic movement, appearing in the iconic West Coast production of Hair before being fired – he claimed – for upstaging the other actors.

By the time he submitted a demo tape to Clive Davis at Columbia Records, he had reinvented himself as Jobriath Boone and developed a different form of songwriting from his earlier work. He also suffered a nervous breakdown during six months in jail for going AWOL from the U.S. Army in the ‘60s. Davis didn’t like the tape – but Jerry Brandt, the impresario best known for bringing the Rolling Stones to America and discovering Carly Simon – overheard the music and became convinced Jobriath was the future.

“What I would like to be is an art form myself instead of art being an extension of myself,” the budding star told Interview. “When I say that I am sexually present onstage, that presence should be a knockout. I paint on my face and body as well as on canvas. … There’s a lot of people running around, putting makeup on and stuff, just because it’s chic. I just want to say that I’m no pretender.”

He outlined his ambition for live performances: “One thing’s for sure: Everybody’s going to be entertained, and nobody’s going to know who they are and they won’t care – neither will I.” Emphasizing his key point, he repeated, “I become a true fairy onstage.” Asked if he meant like Puck in Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, he replied, “No, like Tinkerbell.”

Brandt predicted that “The kids will emulate Jobriath because he cares about his body, his mind, his responsibility to the public as a leader, as a force, as a manipulator of beauty and art.” The talk was big, with Elektra Records allegedly signing him for $500,000 – an unheard-of (and doubted) first deal at the time – and Jobriath certainly aimed to equal it with his musical output. His self-titled debut album, released in 1973, was no toe-in-the-water escapade. It featured Peter Frampton in a guest role and Jimi Hendrix’s engineer Eddie Kramer behind the desk.

“The material just impressed me by its complexity, sensitivity, breadth and quirkiness,” Kramer later told The New York Times. “He was a genius. … He was a romantic soul, really. He wanted orchestrations like old film music, though he knew nothing about scoring. So he bought a book on orchestration and within a week he’d come up with scores of a haunting quality. These were recorded in Olympic Studios in London with a nine-foot grand piano and a 55-piece orchestra.”

Listen to Jobriath’s Self-Titled Debut Album

One of the problems was that, perhaps in over-excitement, Brandt put the horse before the cart in terms of promotion. Provocative seminude pictures of Jobriath appeared everywhere, while Brandt compared him with Elvis Presley, the Beatles and Frank Sinatra, long before there was any music to hear. By the time the album arrived, no one was sure how to match what they’d been told with what they were hearing.

The material presented on Jobriath is most definitely ‘70s art-rock but in step with the best minds in the artist-as-art genre. Joe Elliott of Def Leppard, an early fan who liked the cover of Jobriath’s second album so much he stole it from a shop and later lifted the LP from another location, described the tracks as fresh and exciting. “It was Ziggy Stardust sung by Mick Jagger,” he noted. He said he wasn’t put off by Jobriath’s Bowie-esque visuals (Jobriath dressed as Pierrot the clown nearly a decade before Bowie did). “There was this time in the ‘70s when you did buy albums because the sleeve was cool. … He looked like an alien, and everyone used to always refer to Bowie as an alien. … It looked pretty cool.

“It was exactly what I wanted it to be. It was art-rock, very ‘70s, very music hall. … I can hear a vast difference now, but at the time I wanted it to be like [Bowie, Queen and others].”

But the work wasn’t translating into record sales, and as a result, a three-night extravaganza at a Paris theater – set to cost $200,000 and to be recorded for future release – was canceled. Jobriath had outlined the opening scene: “I’ll be dressed like King Kong, and I’ll swing from a rope onto a replica of the Empire State Building. We’re trying to work it out so that the Empire State Building will turn into a squirting penis, which will feature a piano and stairs for me. As I descend the penis, I’ll turn into a Marlene Dietrich look-alike.”

When Jobriath appeared on The Midnight Special in 1974 – a more muted performance than his plans suggested – the response was equally muted: No one knew how to take his performance. One of his band members, while praising the music, said the costumes and sets Jobriath designed left them looking like “performing monkeys” rather than the real rock band they were. He regretted that, until Brandt’s involvement, it was about the music; afterward, it was all about image.

Watch Jobriath Perform ‘I’maman’

In 1974 Brandt finally arranged a tour, seemingly facing up to the fact that a concept like Jobriath’s had to be an immersive experience to be enjoyed. But that’s when the prejudice kicked in. The first two shows, to sold-out audiences of 400, went perfectly, but in the third performance, “the crowds immediately bombarded him with shouts of ‘f—–’ as trash was thrown until he fled the stage.” It seemed to break some kind of spell, because Elektra pushed out the second album, Creatures of the Street, gave it no promotional support and then dropped him. At the age of 28, Jobriath’s rock ’n’ roll ambitions were over. He slipped into obscurity, surfacing later as Cole Berlin, a New York City cabaret singer, but he often struggled for money and reverted to prostitution, just as he had done during his early days.

“Jobriath committed suicide in a drug, alcohol and publicity overdose,” the artist formerly known as Jobraith said in a rare interview in 1979. “ That whole hype just drove him crazy. He was meant for hype. … His lifestyle was hotel suites and limousines and enough drugs to get him from one to the other. He struck back by disappearing in thin air. Jobriath is dead, but he had a reason for being. … Schizophrenia is my lifestyle. I think everybody is schizophrenic, but they’re all fighting it.

He reflected that “Mr. P.T. Barnum Brandt was so busy getting his name on posters and buses, he neglected to get me on tour or get my album played. … That is probably why Jobriath didn’t make it, even though in 1973 he came up with ‘World Without End,’ one of the first disco tunes.” Jobriath added one of his personalities was writing a Broadway musical “about a pop star, and about hype, and … about America.”

In the case of an artist who wants to be their art, explanations for why they do what they do are seldom available. So it’s not easy to work out what Jobriath wanted to achieve and whether he had achieved it. It’s intriguing to speculate on whether he would have made the big time if he started in Britain, which seemed more accepting of artists like him.

English singer Marc Almond said in 2012, “For me, above all else, he was a sexual hero: truly the first gay pop star. How extreme that was to the U.S. at the time. His outrageous appearances on … Midnight Special prompted shock, bewilderment and disgust. Everyone hated Jobriath – even, and especially, gay people. He was embarrassingly effeminate in an era of leather and handlebar mustaches.”

Listen to Jobriath’s ‘Liten Up’

Jobriath didn’t live to hear such praise. He died in 1983 at 36, one of the first artists to fall victim to the AIDS pandemic. He had become so reclusive that his body wasn’t found in his home for several days after he died. His work began to resurge in 2004 when Morrissey – failing to find him to offer him a tour support slot – discovered he had died and oversaw the reissue of his records. Def Leppard covered Jobriath’s song “Heartbeat” in 2006. In 2012 director Kieran Turner released the documentary Jobriath A.D., which blamed Brandt for much of what went wrong.

But the manager countered that he “was enthralled by [Jobriath]. I thought he was a genius, and I did what I did. The music didn’t sell – that was the bottom line. All the other people who have their opinions were not in the trenches. … Image-wise I didn’t guide him at all; he guided me. I’m a heterosexual, so I don’t think gay. I don’t know what a ‘true fairy’ is – I couldn’t make up those lines if I tried.” He said he didn’t know much about his protege’s past but “saw a lot of darkness. … He was an alcoholic; he was an addict. … If I didn’t protect him, he’d be in jail or he’d kill somebody or be killed.”

Turner agreed, noting, “I think it’s really easy to blame, to put Jerry on the spot and make him a scapegoat. I felt, going in, that Jerry wasn’t to blame. … It was a perfect storm of all these things that came together. … It was ahead of its time and that’s why it failed. … It was much too complex to blame on one thing.”

Listen to Jobriath’s ‘I Love a Good Fight’

In an interview with the Gay Times, Turner argued it may have worked some years after it was tried: “People were not hyped like that back then, especially without having heard the music. It was 180 degrees different from how it is today. Albums took months to break, music acts got two or three albums to try and see how they would fare with the public.”

He said the message transmitted was “too gay, too much hype, too bizarre, noncommercial music, a label who wasn’t paying attention – it all contributed and it ruined him. … The issue with Jobriath is, I think, that he was scared of success. …Though it pains me to say so, I think it’s absolutely on the mark to say that his death was part of his legacy.”

Watch Jobriath Perform ‘Rock of Ages’

Elliott defended Jobriath’s brave attempt at blazing a trail others later followed. “The ‘80s needed the ’70s to set it all up,” he told Yahoo. “The ’70s was full of bands playing with makeup: [Marc] Bolan, Bowie, even the Sweet. Color TV had only just kicked in – in the U.K., at least – so all these bright colors put you ahead of the competition.” On the subject of Jobriath’s apparent failure, he noted, “I believe it’s a combination of different factors, but the most obvious is it just needed time [for rock ’n’ roll androgyny] to sink in.”

Almond reflected that “for all the derision and marginalization he faced, Jobriath did touch lives. He certainly touched mine. … The pretty blond boy with hopes and dreams, carefree and gay, got lost in the dressing-up box. He was born too early and lost too soon.”

35 LGBTQ Icons

A look at some of music’s queer trailblazers.